New ways of teaching controversial history at PTI member, Lancaster Royal Grammar School

Clare O’Sullivan Head of Education Strategy and Development talks to Hugh Castle Head of History and Chair of Trustees of Parallel Histories at a conference at Lancaster Royal Grammar School

1. Clare: So what are you doing here that is innovative?

Hugh: Three things, first we are teaching history as a two competing narratives, not just for one lesson, but all the way through the topic, and second, we are structuring our teaching around a series of debates about particularly controversial events, and third, we rely on interactive videos rather than textbooks to prepare the students.

2. Clare: You’ve really focused on the history of Israel and Palestine, why is that?

Hugh: There are a number of reasons;

First, the history of Israel and Palestine itself is fascinating in its own right. It illustrates so many big ideas, the power of religious belief, imperialism, nationalism, the Cold War, etc.

Second, it’s an area of the world where the history is completely lived and breathed. Sometimes you get the feeling talking to people who live there, that the past is more alive to them than the present; it's like Northern Ireland except amplified, and that for a history teacher is magic.

Third; it's a topic which fascinates Muslim and Jewish students, and a lot of Christian students too, especially the more curious ones. When students enter the classroom with their own views it makes teaching more challenging in some ways of course, but also easier because the students' start point is 'I'm interested'.

Fourth, because it's a controversial subject it's also a great opportunity to teach students the critical and analytical skills they need to evaluate the relative weight of competing evidence, as well as develop an appetite to engage with very different interpretations. I think those skills help to make young people better citizens.

3. Clare: Presumably the Middle East is a popular topic at GCSE and A Level?

Hugh: You would certainly think so but the exact opposite is true. It’s almost disappeared of the exam curriculum – in fact last year only 2,000 students studied it at GCSE out of a cohort of nearly 500,000. It used to be much more popular. That’s why we’ve focused this conference on Year 9.

4. Clare: What’s happened? It’s not as though the conflict in the Middle East has become less relevant?

Hugh: There’s a History Association report from about a dozen years ago which said that there’s a problem in that teachers are shying away from teaching controversial subjects in the classroom, and their predictions have come true. Two of the big three exam boards have dropped the Middle East at GCSE because of lack of demand from schools, and once it’s gone it’s hard to get back. I think we are missing a real opportunity. There are one or two encouraging noises from the government recently about the importance of tackling controversial topics in the classroom – in fact in one training video from Ofsted, teaching Israel and Palestine was offered as ‘best practice’, but we have a long way to go.

5. Clare: So how do you make it easier for teachers to teach this?

Hugh: We incubated and have now spun off an educational charity called Parallel Histories (www.parallelhistories.org.uk) which is designed to do exactly that. It creates videos telling the histories as two parallel narratives. This allows the teacher to facilitate discussion of alternative interpretations rather than having to stand at the front and try to act as arbiter. The students love using them – the videos are interactive and are embedded with primary sources, and we often use them for homework to set up debate and discussion in class.

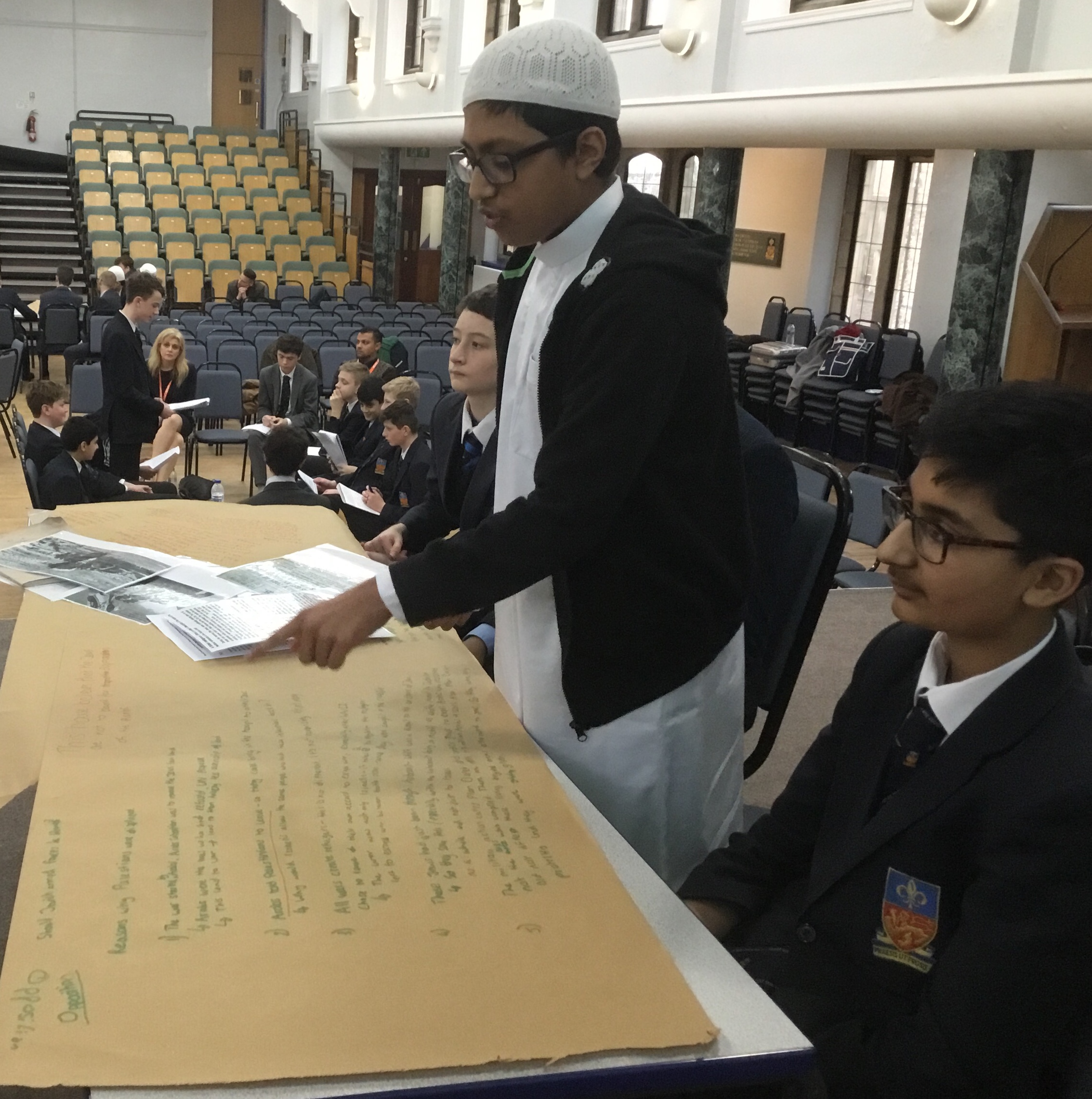

6. Clare: You have a large group of Year 9 students today from a range of local schools today but I see a lot of Sixth Formers here. What do the students all get from it?

Hugh: I think at Year 9 the students really like being challenged to pick through evidence and make arguments, and they like the competitive element of debating, plus of course, making each student contribute keeps everyone focused.

For the Sixth Formers, who are chairing the debates, engaging with both narratives is a lesson in how history is often constructed not to tell the plain unvarnished truth, but to make an argument, to justify a past act, or perhaps to consolidate for a loss. They can feel how, without any disagreement on the facts of what happened, two opposing histories get written. And learning how to detect that process at work is an important skill in our world of fragmented media and so called ‘alternative facts’. And it fits our philosophy of making sure that when our students leave school we have taught them how to think, not what to think.

7. Clare: How do you know it’s working?

Hugh: Well at one level as a teacher you just know from looking at a group of Year 9 students if they are learning or not, but we are a bit more scientific than that too! We survey attitudes and knowledge before and after, sometimes using Survey Monkey, so they can do it on their phones on the bus or at home, and we discuss the results with them so they can understand the process they’ve been using.